Shortly after its discovery, it was recognized that ionizing radiation can have adverse health effects. See Alpen, Introduction. In this section we examine the radiation dose that is a natural part of our environment, and the types of health effects associated with large acute exposures and with low dose rate chronic exposure.

Basic law of radiobiology

Early in the use of ionizing radiation, harmful effects were observed in individuals who had been exposed to large and repeated doses. In 1906 Bergonie and Tribondeau developed a hypothesis, since termed the Basic Law of Radiobiology, regarding biological effects of radiation: Biological effects are directly proportional to the mitotic index and the mitotic future of the exposed cell, and inversely proportional to the degree of differentiation. Mitosis refers to the natural division of a cell nucleus during cell reproduction; differentiation refers to the cell’s degree of specialization to perform a specific function in the organism.

Cell sensitivity

Following this law, the most sensitive cells include rapidly dividing, undifferentiated stem cells such as erythroblasts, intestinal crypt cells, primary spermatogonia, and basal cells in the epidermis. Rapidly dividing cells that are more differentiated, including intermediate stage spermatogonia and myelocytes, are less sensitive than undifferentiated cells but are still quite radiosensitive. Irregularly dividing cells such as endothelial cells and fibroblasts demonstrate intermediate sensitivity. Cells that do not normally divide but have the potential for division, such as parenchymal liver cells are relatively radioresistant. Non‐dividing cell lines such as muscle cells, nerve cells, mature erythrocytes, and spermatozoa are the most radioresistant. Some cells that would be predicted to be resistant to damage because they do not undergo division and are differentiated, such as the lymphocytes and ova, are nonetheless quite radiosensitive.

DNA as the target

All these cells appear to be affected because of DNA lesions and double strand breaks. The target in the lymphocytes and ova appears to be lipoprotein structures in the nuclear cell membrane rather than in the DNA itself. Damage can be produced directly by the interaction of the radiation with the biochemical target, or by interactions of the free radicals OH, e‐aq, and H that are the ionization products of water which have unpaired electrons, with the DNA or other targets. See Turner ch. 13.

Age, species, and fractionation

Other factors affect radiosensitivity. As expected, radiosensitivity is greatest during the fetal stage and becomes progressively smaller through adolescence and adulthood. Different species demonstrate different radiosensitivities. A large acute dose delivered at once would have a greater effect than the same dose administered over time as incremental fractions.

Rad and Rem

The US unit of dose is the rad; it is the deposition of 100 ergs of ionizing energy per gram of target material. The US unit of dose equivalent is the rem; for x‐, gamma‐, and beta‐radiation it is numerically equal to the dose in rad. Both are approximately equal to the exposure in roentgen. There are rad‐to‐rem correction factors as high as twenty to account for the greater radiation damage caused by alpha particles, neutrons, and high energy protons.

Gray and Sievert

The SI units for dose and dose equivalent are the gray (Gy) and sievert (Sv). 1 Gy = 100 rad. 1 Sv = 100 rem. The centigray equal to one rad and the millisievert equal to 100 millirems are commonly used.

Average natural background dose

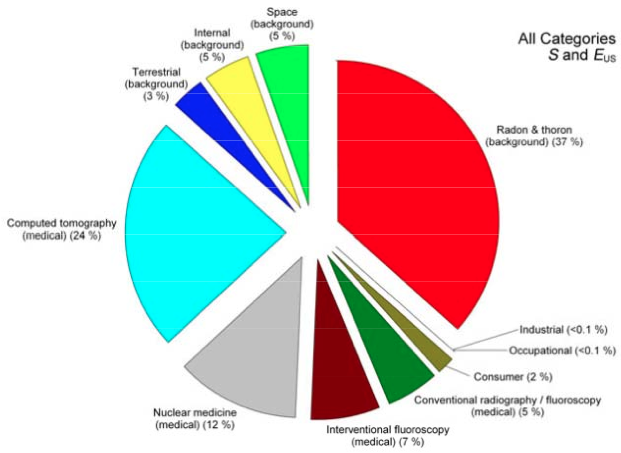

The amount of radiation an individual receives is called the dose equivalent and is measured in rems. The average individual in the United States accumulates a dose equivalent of 0.3 rem from natural sources each year. Figure 1.11.

Variations in natural background

Natural background radiation levels are much higher in certain geographic areas. A dose of 1 rem may be received in some areas on the beach at Guarapari, Brazil in about 9 days. Some people in Kerala, India get a dose of 4 rems every year. In the US, the dose from natural radiation is higher in some states, such as Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota, primarily because of increased cosmic radiation at high elevations and natural high concentrations of uranium and thorium in the soil. Radiation dose can also be received from brick structures, from consumer products, and from air travel.

Medical Dose

Many people receive additional radiation for medical reasons. As of the year 2006, approximately 400 million x‐ray radiography examinations are performed in the United States. A typical two view chest x‐ray leads to an effective exposure of about 20 mRem. CT examinations deliver much higher doses than standard x‐rays. A typical whole trunk CT (chest, abdomen and pelvis) can be 1.5 rem.

Deterministic effects (also known as nonstochastic effects)

A clinically observable biological effect that occurs days to months after an acute radiation dose is a deterministic effect. Examples are skin reddening or swelling, epilation, or hematologic depression. Deterministic effects require a dose that is greater than a threshold, typically greater than tens or hundreds of rad. Dose limits are set so that occupational exposures will not cause deterministic effects. Examples are dose limits for the lens of the eye (15 rem each year) and for any single organ (50 rem each year).

FIGURE 1.11 SOURCES OF RADIATION DOSE IN THE UNITED STATES. From NCRP 160, Fig 1.1. Percent contribution of various sources of exposure to the total collective effective dose (1,870,000 person‐Sv) and the total effective dose per individual in the U.S. population.

Deterministic effects are possible when using electronic devices such as x‐ray diffraction units (XRDs) or linear accelerators. An XRD beam is sufficiently intense to cause skin burns and ulceration that ultimately require amputation. The broad beam of a linear accelerator could cause cataracts or a lethal whole body dose within minutes. Thus it is imperative that interlocks and other safety features never be bypassed.

Stochastic effects

Radiation dose can increase the chance of contracting a cancer. This is an example of a stochastic effect. The increase in chance is assumed to be proportional to the dose, and it is assumed there is no minimum threshold. These two assumptions lead us to low worker and public dose limits. Scientists disagree on whether this conservative linear non‐threshold, or LNT, model is the best mathematical representation of the risk of cancer induction. The normal incidence of fatal cancer in an average North American population sample of 10,000 individuals is about 2000. If each individual in the sample were exposed to a 1 rem whole body dose, it is estimated there would be about 4 additional fatal cancers. See BEIR V ch. 3‐5.

Tissue weighting factors

In setting limits for doses to individuals, the LNT model also has been used to develop a factor that compares the cancer risk of dose to an individual organ to cancer risk of dose to the whole body. This is of interest when a single organ receives dose after ingestion of radioactivity, or when your body trunk is shielded with a lead apron but the head, neck, and arms are exposed. When the organ dose in rad is multiplied by the tissue weighting factor, the product is the effective dose or effective dose equivalent in rem. This allows a single, risk‐based additive dose quantity to be used to limit and record all exposures from penetrating radiation from outside the body and radioactivity inside the body.

Hereditary effects

A hereditary effect is one transmitted to offspring due to the irradiation of the parent egg or sperm cells. Although, it has been estimated based on experimental organisms that the chance of a severe hereditary effect is between 0 and 0.00006 per rem, the UNSCEAR 2001 Report on the hereditary effects of radiation emphasized that no radiation‐induced hereditary diseases have so far been demonstrated in human populations exposed to ionizing radiation. The normal chance of a birth defect is 0.03, about one‐fourth of which is considered of genetic origin.

Basis for dose limits

Radiation, like many things, can be harmful. A large dose to the whole body (such as 600 rems in one day) would probably cause death in about 30 days; but such large doses result only from rare accidents. Control of exposure to radiation is based on the assumption that any exposure, no matter how small, involves some risk. The 5‐ rem worker dose limit provides a level of risk of delayed effects that is considered acceptable by the NRC. The dose limits for individual organs are below the levels at which biological effects are observed. Thus the risk to individuals at the occupational exposure levels is considered to be very low. However, it is impossible to say that the risk is zero. See ICRP 60, Sec. 5. Thus our goal is to keep all radiation dose as low as reasonably achievable below the limits; see the discussion on p.23.

Dose limit for radiation workers

As a radiation worker, you may be exposed to more radiation than the general public. California and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) have established a basic dose limit for all occupationally exposed adults of 5 rems each year.

Dose limit for minors and public

Because the risks of undesirable effects may be greater for young people, individuals under age 18 are permitted to be exposed to only 10 percent of 5 rem, the adult worker limits.

The limit for members of the general public is 0.1 rem.

Dose limit for pregnant workers

The National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements has recommended that, because they are more sensitive to radiation than adults, radiation dose to the unborn that results from occupational exposure of the mother should not exceed 0.5 rem. California and the NRC have incorporated this recommendation in their worker dose limit regulations. See Table 2.1.

It is your responsibility to decide whether the exposure you are receiving from penetrating radiation and intake is sufficiently low. Contact Health Physics to determine whether radiation levels in your working areas could cause a fetus to receive 0.5 rem or more before birth. Health Physics makes this determination based on personnel exposure monitor reports, surveys, and the likelihood of an accident in your work setting. Very few work positions would require reassignment during pregnancy.

If you are concerned about exposure risk, you may consider alternatives:

a) If you are pregnant, you may ask to be reassigned to areas involving less exposure to radiation. Approval will depend on the operational needs of the department. Note, however, that no employer is required to provide a work environment that is absolutely free of radiation.

b) You could reduce your exposure, where possible, by decreasing the amount of time you spend in the radiation area, increasing your distance from the radiation source, and using shielding. Increased concern for lab cleanliness will reduce the chance of uptake.

c) You could delay having children until you are no longer working in an area where the radiation dose to your fetus could exceed 0.5 rem.

d) You can continue working in the higher radiation areas, but with full awareness that you are doing so at some small increased risk for your fetus.

Discuss these alternatives with your supervisor and Health Physics. A pregnancy declaration form appears in Forms. There is additional information in the discussion of dose limits in Chapter 2 of this manual.