Gamma rays and x‐rays

Gamma rays and x‐rays are both forms of electromagnetic radiation. They differ only in their source. A gamma ray emanates from the nucleus of a radioactive atom. An x‐ray emanates from outside the nucleus of a radioactive atom, or from an electron as it changes direction when passing an atomic nucleus; this latter type of x‐ray is called bremstrahlung. All are collectively referred to as ionizing photons.

Photon interactions

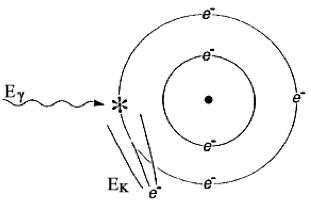

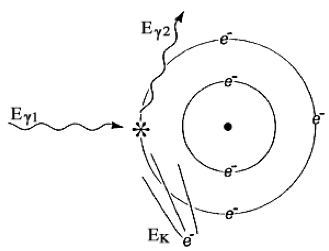

Because it is not charged, a photon does not interact by coulumbic force, but rather only by interaction with an electron. The two most common forms of interaction are the photoelectric effect, .Figure 1.5, and Compton scattering, Figure 1.6.

The probability of these events depends on the absorbing medium and the photon energy. The photoelectric effect predominates for low energy photons (less than 100 keV). Its probability increases dramatically with Z. The Compton effect predominates for moderate to high energy photons (more than 100 keV). See Hendee ch 4. These facts drive our selection of shielding materials.

FIGURE 1.5 THE PHOTOELECTRIC EFFECT. The photon is completely absorbed. Its energy Eγ liberates an electron bound with energy EB, and provides it with kinetic energy EK. Mathematically, EΚ = Eγ ‐ EB

FIGURE 1.6 COMPTON SCATTER. An incident photon with energy Eγ1 liberates an orbiting electron, yielding a recoil electron with kinetic energy EK and a lower energy scattered photon with energy Eγ2 Mathematically, Eγ1 = EK + Eγ2

Other interactions

Low energy photons can also interact by coherent scattering. High energy photons can also interact by pair production and photodisintegration. Coherent scattering is generally not of interest in radionuclide laboratory setting and will not be discussed. High energy interactions are of interest in shielding high energy accelerators.

Attenuation

The reduction of intensity I of a photon flux is called attenuation. The mathematics of attenuation of ionizing photons in an absorber is identical to the mathematics of half‐life. However, we use the terms thickness x, half value layer HVL, and linear attenuation coefficient μ in place of time t, half‐life T1/2, and decay constant λ. If one half value layer of shielding is added, the dose rate will be reduced by one‐half. For a shielding thickness x, the intensity can be described mathematically:

Ix = I0 e‐.693 x/HVL

e‐.693 is equal to 1⁄2, and the exponent x/HVL describes the number of half value layers. Alternatively, if n is the number of half value layers, then:

Ix = I0 (1/2)n

Half value layers typically range from millimeters to centimeters, depending on the energy of the radiation and the elemental composition of the attenuating medium. Glass, concrete, steel, lead, and depleted uranium are all commonly used as shielding. See Figure 1.9.

As noted before for half‐life and decay constant, the half value layer and linear attenuation coefficient are related: μ = .693/HVL. Thus, we can also write:

Ix = I0 e‐μx

When using either equation, be sure that the same unit of thickness, whether centimeters or millimeters, is used to measure both HVL and attenuation constant, and applied thickness.